In January, I was laid off from my position as a software developer at REI. Since then, I’ve dedicated more time to developing my AI-powered Game Master tools, which started as a passion project. To support this endeavor, I started a Patreon to help cover the costs associated with ChatGPT API calls, without focusing much on monetization initially. However, as I pouring more effort into these tools, I’m shifting towards a freemium model.

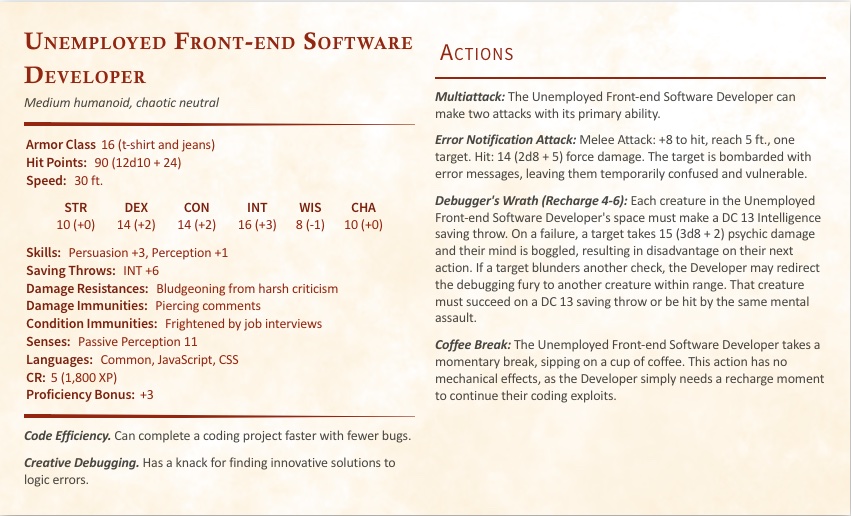

This change hasn’t been implemented yet, but I want to share what you can expect. The most popular app, the D&D 5e Statblock Generator, which use templates from D&D 5th edition SRD monsters, will soon have a daily usage limit. Users will be able to generate up to five statblocks per 24-hour period. This limit should accommodate the average user based on my surveys, which show most generate zero to five statblocks weekly.

For those who need more extensive access, a subscription at the $5 or Master Worldshaper level will remove this limit. This adjustment also allows me to potentially make other tools, like the dungeon generator, free for all users while reserving more complex features, like enhanced statblock generation for the npcs that appear in the dungeons, for patrons.

These changes are designed to strike a balance between making the tools accessible and supporting their continued development and my livelihood. If you are excited about these updates or if you’re connected to software development opportunities, please do not hesitate to reach out. My LinkedIn address is here: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kenjicrosland/. I am also eager to hear your feedback and ideas for future enhancements to the Game Master tools.

Thank you for your ongoing support and enthusiasm for the apps.